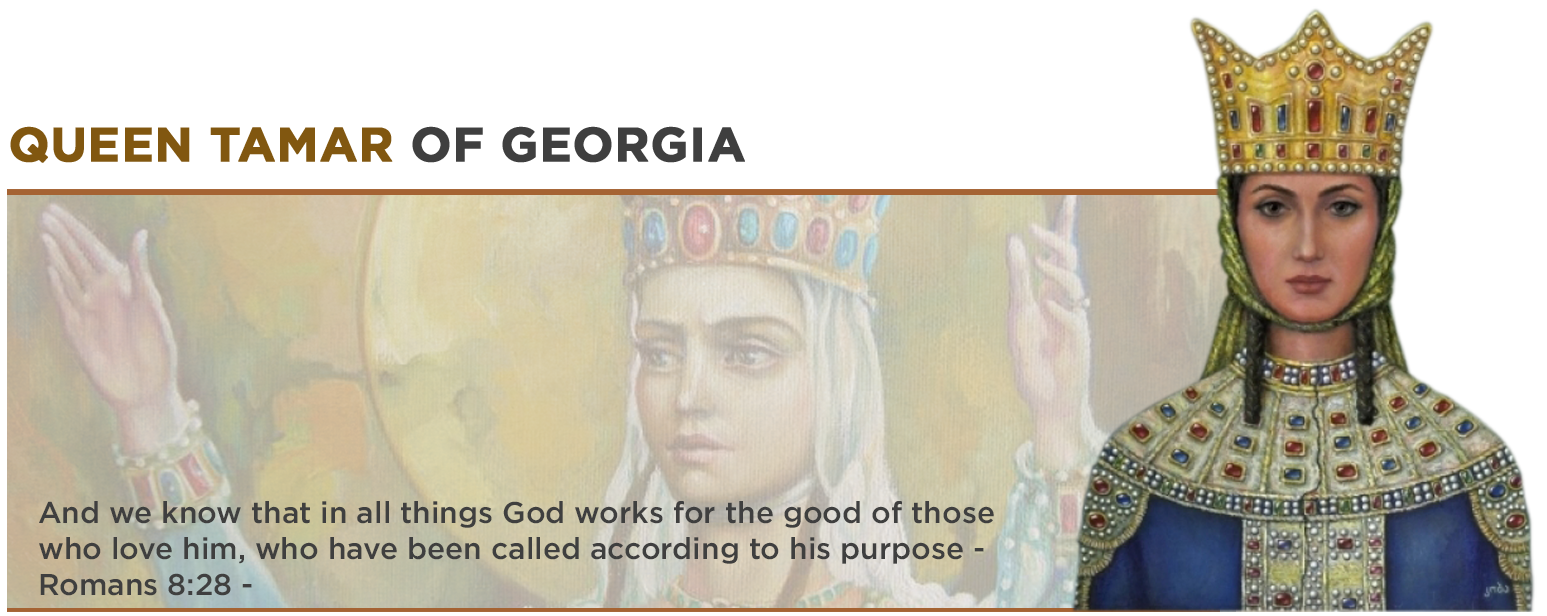

Tamar the Great (c. 1160 – 18 January 1213) reigned as the Queen of Georgia from 1184 to 1213, presiding over the apex of the Georgian Golden Age. A member of the Bagrationi dynasty, her position as the first woman to rule Georgia in her own right was emphasized by the title mepe ("king"), afforded to Tamar in the medieval Georgian sources. Tamar was the granddaughter of Georgia’s greatest king David IV, also known as David the Builder. The name Tamar is of Hebrew origin and, like other biblical names, was favored by the Georgian Bagrationi dynasty because of their claim to be descended from David, the second king of Israel.

Tamar was proclaimed heir and co-ruler by her reigning father George III in 1178. For six years, Tamar was a co-ruler with her father upon whose death, in 1184, Tamar continued as the sole monarch and was crowned a second time at the Gelati cathedral near Kutaisi, western Georgia. However, she faced significant opposition from the aristocracy upon her ascension to full ruling powers after George's death. The energetic involvement of Tamar's influential aunt Rusudan and the Catholicos-Patriarch Michael IV was crucial for legitimizing Tamar's succession to the throne. However, the young queen was forced into making significant concessions to the aristocracy. She had to reward the Catholicos-Patriarch Michael's support by making him a chancellor, thus placing him at the top of both the clerical and secular hierarchies.

Relying on a powerful military élite, Tamar was able to build on the successes of her predecessors to consolidate an empire which dominated the Caucasus until its collapse under the Mongol attacks within two decades after Tamar's death.

Tamar was married twice, her first union being, from 1185 to 1187, to the Rus' prince Yuri, whom she divorced and expelled from the country, defeating his subsequent coup attempts. For her second husband Tamar chose, in 1191, the Alan prince David Soslan, by whom she had two children, George and Rusudan, the two successive monarchs on the throne of Georgia, George-Lasha, the future king George IV was born 1192 or 1194 and their daughter, Rusudan, was born c. 1195.

Tamar's association with the period of political and military successes and cultural achievements, combined with her role as a female ruler, has led to her idealization and romanticization in Georgian arts and historical memory. She remains an important symbol in Georgian popular culture and has been canonized by the Georgian Orthodox Church as the Holy Righteous Queen Tamar with her feast day commemorated on 14 May (O.S. 1 May). Tamar was born in circa 1160 to George III, King of Georgia, and his consort Burdukhan, a daughter of the king of Alania. The name Tamar is of Hebrew origin and, like other biblical names, was favored by the Georgian Bagrationi dynasty because of their claim to be descended from David, the second king of Israel.

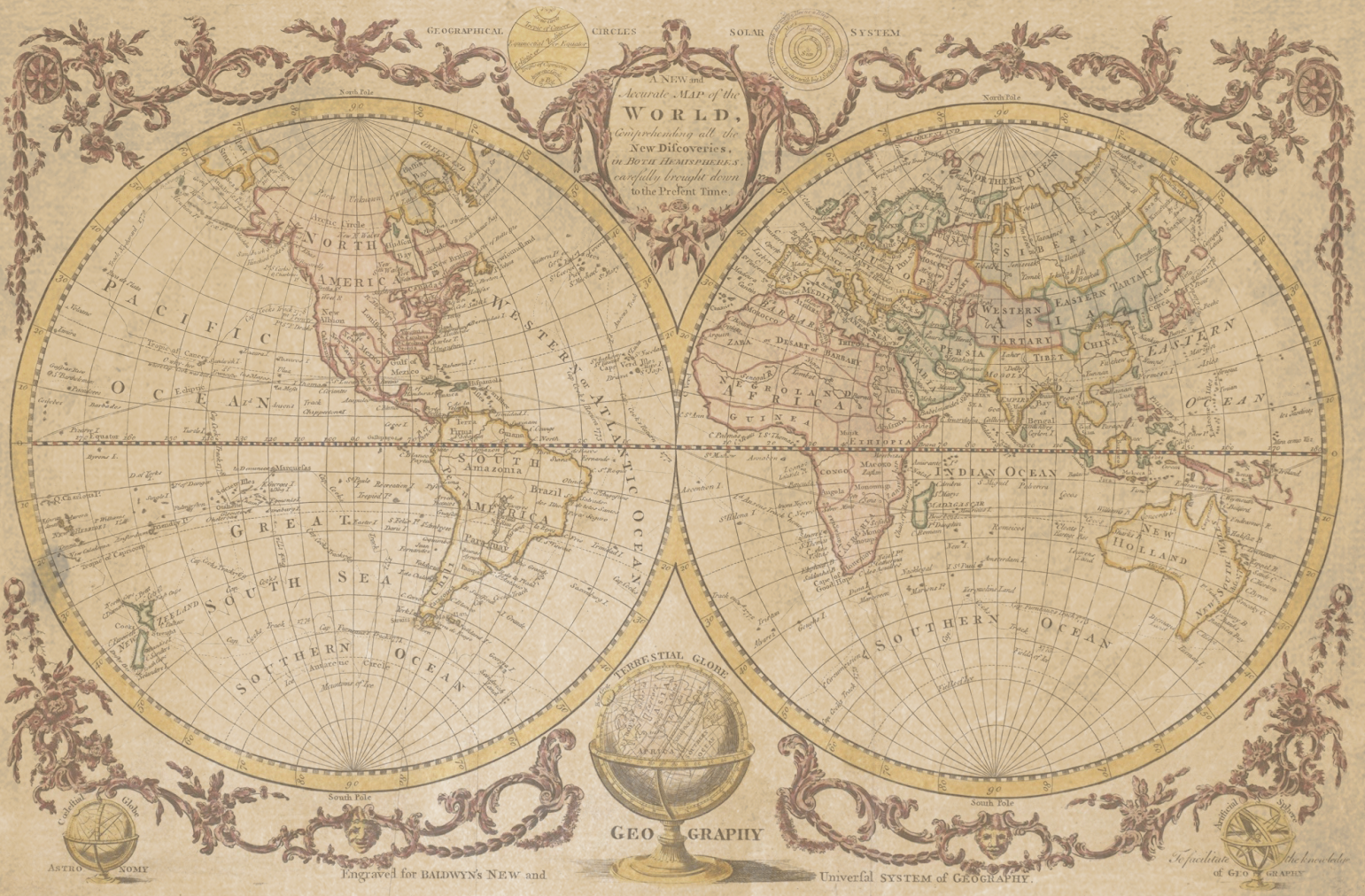

Among the remarkable events of Tamar's reign was the foundation of the Empire of Trebizond on the Black Seacoast in 1204. This state was established by Alexios I Megas Komnenos (r. 1204–1222) and his brother, David, in the northeastern Pontic provinces of the crumbling Byzantine Empire with the aid of Georgian troops. Alexios and David, Tamar's relatives, were fugitive Byzantine princes raised at the Georgian court. According to Tamar's historian, the aim of the Georgian expedition to Trebizond was to punish the Byzantine emperor Alexios IV Angelos (r. 1203–1204) for his confiscation of a shipment of money from the Georgian queen to the monasteries of Antioch and Mount Athos. However, Tamar's Pontic endeavor can better be explained by her desire to take advantage of the Western European Fourth Crusade against Constantinople to set up a friendly state in Georgia's immediate southwestern neighborhood, as well as by the dynastic solidarity to the dispossessed Komnenoi. Tamar sought to make use of the weakness of the Byzantine Empire and the Crusaders' defeat at the hands of the Ayyubid sultan Saladin in order to gain Georgia's position on the international stage and to assume the traditional role of the Byzantine crown as a protector of the Christians of the Middle East. Christian Georgian missionaries were active in the North Caucasus and the expatriate monastic communities were scattered throughout the Eastern Mediterranean. Tamar's chronicle praises her universal protection of Christianity and her support of churches and monasteries from Egypt to Bulgaria and Cyprus.

The Georgian court was primarily concerned with the protection of the Georgian monastic centers in the Holy Land. By the 12th century, eight Georgian monasteries were listed in Jerusalem. Saladin's biographer, Bahā' ad-Dīn ibn Šaddād, reports that after the Ayyubid conquest of Jerusalem in 1187, Tamar sent envoys to the sultan to request that the confiscated possessions of the Georgian monasteries in Jerusalem be returned. Saladin's response is not recorded, but the queen's efforts seem to have been successful: Jacques de Vitry, who attained to the bishopric of Acre shortly after Tamar's death, gives further evidence of the Georgians’ presence in Jerusalem. He writes that the Georgians were – in contrast to the other Christian pilgrims – allowed a free passage into the city, with their banners unfurled. Ibn Šaddād furthermore claims that Tamar outbid the Byzantine emperor in her efforts to obtain the relics of the True Cross, offering 200,000 gold pieces to Saladin who had taken the relics as booty at the Battle of Hattin – to no avail, however.

Georgia's political and cultural exploits of Tamar's epoch were rooted in a long and complex past. Tamar owed her accomplishments most immediately to the reforms of her great-grandfather David IV (r. 1089–1125) and, more remotely, to the unifying efforts of David III and Bagrat III who became architects of a political unity of Georgian kingdoms and principalities in the opening decade of the 11th century. Tamar was able to build upon their successes. By the last years of Tamar's reign, the Georgian state had reached the zenith of its power and prestige in the Middle Ages. Tamar's realm stretched from the Greater Caucasus crest in the north to Erzurum in the south, and from the Zygii in the northwest to the vicinity of Ganja in the southeast, forming a pan-Caucasian empire, with the loyal Zachariad regime in northern and central Armenia, Shirvan as a vassal and Trebizond as an ally. A contemporary Georgian historian extols Tamar as the master of the lands "from the Sea of Pontus [i.e., the Black Sea] to the Sea of Gurgan [i.e., the Caspian Sea], from Speri to Derbend, and all the Hither and the Thither Caucasus up to Khazaria and Scythia."

The royal title was correspondingly aggrandized. It now reflected not only Tamar's sway over the traditional subdivisions of the Georgian realm, but also included new components, emphasizing the Georgian crown's hegemony over the neighboring lands. Thus, on the coins and charters issued in her name, Tamar is identified as: By the will of God, King of Kings and Queen of Queens of the Abkhazians, Kartvelians, Arranians, Kakhetians, Aremenians, Shrivanshah and Shahanshah; Autocrat of all the East and the West, Glory of the World and Faith; Champion of the Messiah.

The queen never achieved autocratic powers and the noble council continued to function. However, Tamar's own prestige and the expansion of patronq'moba – a Georgian version of feudalism – kept the more powerful dynastic princes from fragmenting the kingdom. This was a classical period in the history of Georgian feudalism.

With this prosperity came an outburst of the distinct Georgian culture, emerging from the amalgam of Christian, secular, as well as Byzantine and Iranian influences. Despite this, the Georgians continued to identify with the Byzantine West, rather than Islamic East, with the Georgian monarchy seeking to underscore its association with Christianity and present its position as God-given. It was in that period that the canon of Georgian Orthodox architecture was re-designed and a series of large-scale domed cathedrals were built.

The contemporary Georgian chronicles enshrined Christian morality and patristic literature continued to flourish, but it had, by that time, lost its earlier dominant position to secular literature, which was highly original, even though it developed close contact with neighboring cultures. The trend culminated in Shota Rustaveli's epic poem The Knight in the Panther's Skin (Vepkhistq'aosani), which celebrates the ideals of an "Age of Chivalry" and is revered in Georgia as the greatest achievement of native literature.

Tamar outlived her consort, David Soslan, and died of a "devastating disease" not far from her capital Tbilisi, having previously crowned her son, Giorgi-Lasha, coregent. Her remains were transferred to the cathedral of Mtskheta and then to the Gelati monastery, a family burial ground of the Georgian royal dynasty. The traditional scholarly opinion is that Tamar died in 1213, although there are several indications that she might have died earlier, in 1207 or 1210.

In later times, a number of legends emerged about Tamar's place of burial. One of them has it that Tamar was buried in a secret niche at the Gelati monastery so as to prevent the grave from being profaned by her enemies. Another version suggests that Tamar's remains were reburied in a remote location, possibly in the Holy Land. The French knight Guillaume de Bois, in a letter dated from the early 13th century, written in Palestine and addressed to the bishop of Besançon, claimed that he had heard that the king of the Georgians was heading towards Jerusalem with a huge army and had already conquered many cities of the Saracens. He was carrying, the report said, the remains of his mother, the "powerful queen Tamar" (regina potentissima Thamar), who had been unable to make a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in her lifetime and had bequeathed her body to be buried near the Holy Sepulchre.

In the 20th century, the quest for Tamar's grave became a subject of scholarly research, as well as the focus of broader public interest. The Georgian writer Grigol Robakidze wrote in his 1918 essay on Tamar: "Thus far, nobody knows where Tamar's grave is. She belongs to everyone and to no one: her grave is in the heart of the Georgian. And in the Georgians' perception, this is not a grave, but a beautiful vase in which an unfading flower, the great Tamar, flourishes." An orthodox academic view still places Tamar's grave at Gelati, but a series of archaeological studies, beginning with Taqaishvili in 1920, has failed to locate it at the monastery.